Welcome back to the Big Law Business column. I’m Roy Strom, and today we look at how Big Law firms are trying to mitigate risks in the SPAC practice. Sign up for Business & Practice, a free morning newsletter from Bloomberg Law.

Big Law learned a lesson about SPACs when the last boom ended: The shell companies are not a blank check for lawyer fees.

That’s because special purpose acquisition companies are a two-step process, and law firms make the bulk of their money on the second step. That is, when a SPAC spends the pile of money it raised to complete a merger and usher a private company onto the public markets.

During the boom of 2021 and 2022, when Big Law firms fell over themselves to cash in on the craze, many SPACs failed to complete a merger. That meant lawyers didn’t get paid the way they’d hoped.

So with activity in the so-called blank check companies heating up again, law firms are approaching with care.

“A lot of law firms took some big write-offs,” said Elliott Smith, a Perkins Coie partner who advises on these transactions. “They were able to absorb those losses within their other countercyclical practices. So yeah, there is a certain caution that is applied now that probably wasn’t in 2021.”

Some firms are sitting out the resurgence, while others are looking to negotiate broken deal fees for mergers—the part of the process known as a de-SPAC—that fail to materialize.

Still others are trying to get their fees for a merger guaranteed as part of the first step—an initial public offering. For that stage of work, law firms generally charge a flat fee of around $250,000 to $400,0000, according to regulatory filings. Legal fees for de-SPACs are typically in the single millions, lawyers have said.

Firms are simply being more selective about what clients they’ll work with in these transactions. They’re looking for SPACs that are more likely to complete a merger (hint: anything with institutional investor backing is a good sign). Or they’ll decide to stick with a transaction because the firm has a broader relationship with a client at stake.

“There is a lot more due diligence, let’s say, by a lot of the bigger firms before they get involved with a de-SPAC transaction,” said Joel Rubinstein, a White & Case partner who has advised on SPACs since 2005. “They are not blindly taking on de-SPAC deals with new clients where you can accrue a multimillion-dollar bill and then get left holding the bag if the deal doesn’t get done.”

One major firm that followed investment banking clients into the SPAC market in 2020 is not actively pursuing the work, according to a partner who described the firm’s strategy on the condition of anonymity. The firm would work for a regular client if it were pursuing a SPAC IPO or a de-SPAC, but so far none have brought those opportunities, the partner said.

One strategy pursued in 2020 involved representing SPAC IPOs for a discounted fee in exchange for an assurance that the firm would advise on the more lucrative de-SPAC transaction, the partner said. Considering how many vehicles failed to complete a merger, “that strategy bears a lot of risk,” the partner said.

Carefully choosing clients is the best way to mitigate any payment risks, said Stephen Alicanti, a DLA Piper partner who has advised on four SPAC IPOs in the past month. At DLA Piper, a special committee assesses each new SPAC-related transaction before lawyers are permitted to engage on a new matter.

It’s “incredibly important” that the latest vintage of SPACs successfully close deals, Alicanti said. “In light of the quality of some of the target companies we’re working with, I’m optimistic that we’re going to start seeing those positive results in the next six to twelve months,” he said.

To be sure, the recent return of SPACs hasn’t reached anywhere near the height of the pandemic-era boom.

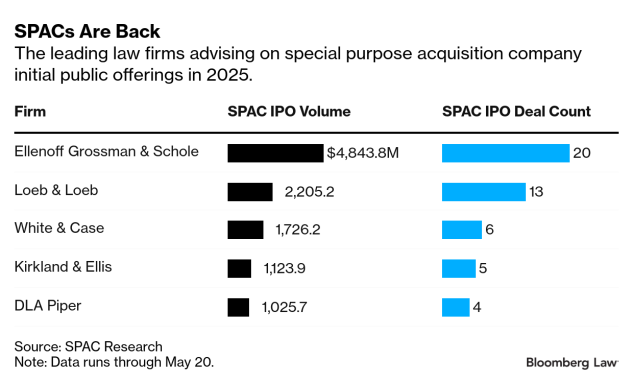

There have been 46 SPAC IPOs so far this year, raising about $9.5 billion, according to data from SPAC Insider. That’s about what was raised all last year.

In 2021, more than 600 SPACs hit the market, building a pool of more than $150 billion searching for companies to take public. Of those, 319 SPACs have been liquidated—most of which never completed a merger, SPAC Insider data show.

Still, some firms see opportunities.

White & Case advised blank-check vehicle Helix Acquisition Corp. II in its $949 million combination with BridgeBio Oncology Therapeutics announced in March. That deal included $260 million in committed financing through what is known as a PIPE, or a private investment in public equity—a sign that institutional investors back the deal’s closing. (SPAC IPO investors can redeem their shares before a merger, effectively pulling their money and increasing the risk that deals will fall through.) The firm also advised the Helix vehicle on its February 2024 IPO.

White & Case’s Rubinstein said SPACs have always been a “meaningful part” of his practice, “so we care about it.”

“There will be other firms that will say it’s not as important,” he said.

Douglas Ellenoff, a champion of the SPAC structure whose firm Ellenoff Grossman & Schole has for years represented the most SPACs, said he expects to handle a larger share of de-SPAC transactions as larger firms grow more conservative.

“The major law firms who have a lot of capacity had a lot of credit risk, and they are not going to do that again because they’re used to being paid for their time,” Ellenoff said. “For us, it’s a venture portfolio. We get paid on some and we don’t get paid on others. That’s the way the SPAC industry operates.”

Perkins Coie’s Smith said he’s “cautiously optimistic” that the most recent SPAC vintage will result in more deals.

“The valuations have come down,” he said, “and there’s more recognition that a company needs to be generating significant revenue in order to make sense as a public company.”

Lawyers, like the rest of the SPAC industry, are invested in seeing successful deals finalized. They’re hoping this time is different than last.

Worth Your Time

On Cadwalader: The law firm aims to help the Brooklyn District Attorney defend convictions as a way to satisfy a pledge to President Donald Trump for free legal services, Justin Henry reports.

On KPMG Law: A California bill aims to throw a wrench into plans by KMPG and law firms backed by outside investors to operate in the state from their perches in Arizona, Emily Siegel reports.

On Susman Godfrey: The law firm is boosting a law student diversity scholarship program that’s under attack by the Trump administration, Tatyana Monnay reports. She also spoke about the firm on Bloomberg Law’s On The Merits podcast.

That’s it for this week! Thanks for reading and please send me your thoughts, critiques, and tips.

To contact the reporter on this story:

To contact the editors responsible for this story:

Learn more about Bloomberg Law or Log In to keep reading:

See Breaking News in Context

Bloomberg Law provides trusted coverage of current events enhanced with legal analysis.

Already a subscriber?

Log in to keep reading or access research tools and resources.