03.03.2016

|

Updates

The federal government took another step in the fight against human trafficking and forced labor. President Obama signed into law on February 24, 2016, the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (TFTEA), which we have previously discussed. This enactment critically closes a loophole by amending the Tariff Act of 1930 (Tariff Act) to remove the long-standing “immunity” for broad classes of goods made with forced, indentured, child or prison labor.

And as the risk of detection increases, so does the very real risk of criminal prosecution under 18 U.S.C. § 545 (prohibiting certain categories of smuggling) and 19 U.S.C. § 1307 (prohibiting importation of products made by or through forced labor).

The International Labor Organization estimates that some 21 million people are “victims of forced labor” and that forced labor annually generates some $150 billion in illegal profits. Therefore, the possibility that, entirely unbeknownst to the U.S. importers, categories of goods may be tainted and denied entry into the United States is significant.

The law takes effect March 10, 2016.

Major Change to Clearance of Imported Goods

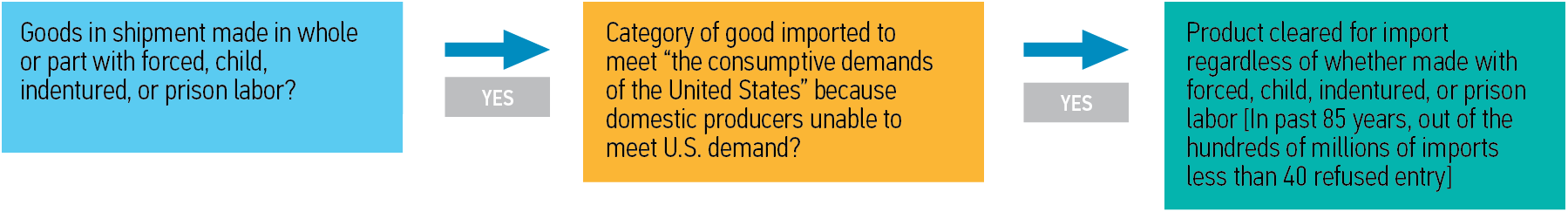

Prior to March 10, 2016, and for the past 85 years, this was how classes of imported goods made with forced, child, indentured and prison labor were evaluated for import clearance.

As of March 10, 2016, these are the new clearance provisions.

Requirements in Tariff Act Amendments

Prohibition on Imports. Under the amended Section 307 of the Tariff Act (and 19 U.S.C. § 1307), all goods made “wholly or in part in any foreign country” through forced, indentured, child or prison labor “shall not be entitled to entry at any of the ports of the United States . . . .” This “wholly or in part” formulation is of particular significance because it means that even “minor” involvement of forced, indentured, child or prison labor in the manufacture of a product may taint the entire product.

Reporting Requirement. Congress also implemented a reporting requirement. The Commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) must now submit annually a report to Congress stating: (1) how many times merchandise was denied entry under the Tariff Act during the prior year; (2) a description of the merchandise; and (3) any other relevant information. The first such report is due to Congress on August 22, 2016.

Removing the Exception that for 85 Years Has Swallowed the Rule

Since the Tariff Act’s passage in 1930, the United States has made it illegal to import any goods made with forced, indentured, child or prison labor. However, a controversial key carve-out provided that certain goods from abroad that met “the consumptive demands of the United States” were exempt from the ban. So, for example, because the demand for cocoa or teak far outstripped any domestic supply (after all, there is none), cocoa and teak imports were never stopped regardless of how the cocoa or teak was harvested or produced.

The impact of the carve-out is far more than academic. For the past 85 years, CBP has reported less than 40 instances of stopping shipments of goods suspected to have been made with forced, indentured, child or prison labor. Given that in many parts of the world forced, indentured, child and prison labor is commonplace, this low number speaks to the carve-out’s real-world impact.

The Bureau of International Labor Affairs at the U.S. Department of Labor maintains an extensive list of goods determined to be produced by child or forced labor. Enforcement challenges will continue. But with the carve-out a thing of the past, every indication is that scrutiny of imports, and the corresponding number of stopped shipments, is likely to increase significantly.

How Are Goods Kept Out?

The TFTEA lacks specific guidance as to its implementation or enforcement. Despite some early reporting to the contrary, there is no reason to believe that all goods included on the U.S. Department of Labor list will be categorically banned, e.g., all “electronics and toys from China,” “cotton from India,” or “garments from Vietnam.”

Instead, we expect U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and CBP to develop a middle-ground, case-by-case approach. Such a common-sense approach will likely be informed by the U.S. Department of Labor list, as well as whistleblower and advocacy organization tips and publicly available information indicating that a particular shipment should be inspected or stopped.

Practical Tips: What Should Companies Do?

Prepare for Broader Enforcement Efforts, Particularly on Imports of “Suspect Goods” from “Suspect Countries.” As of March 10, 2016, the “consumptive demands of the United States” carve-out will be a thing of the past. We believe the CBP enforcers will immediately begin to use as its first line resource the U.S. Department of Labor’s list of 136 suspect goods, which hail from 74 suspect countries, believed to be directly or indirectly tainted by forced or child labor in the supply chain. With the carve-out gone, the Department of Labor’s findings create a de facto “presumption” that these goods will violate the amended Tariff Act.

Avoid Any Taint in Supply Chain. The amended Tariff Act prohibition implicates every piece of a product. Even if one small component in a larger product is made using forced, child, indentured or prison labor, the entire product can be seized. The net result is that use of forced, child, indentured or prison labor in any part of the supply chain, no matter how many steps removed, can potentially result in seizure of goods. In the absence of meaningful due diligence, the danger of such import-prohibiting taint is very real. The most effective step to reduce the chances of seizure of imports is to set up robust compliance programs designed to identify and remove tainted products or components of products from the supply chain.

Prepare Supply Chain Management for its Role in Addressing Compliance Risks.

1. Create a meaningful due diligence process by ensuring that all supplier and subcontractor contracts:

- contain a robust indemnification clause;

- provide audit rights;

- require full cooperation in the case of any internal investigation or review;

- obligate the supplier or subcontractor to immediately notify the company of any actual or potential nonperformance or other problems; and

- require the supplier or subcontractor to consent to follow a company-developed action plan in case of any non-compliance.

2. Require representations and warranties that the supplier or subcontractor:

- is in compliance with all applicable national and international laws and regulations, including U.S. Customs laws and regulations, as well as the company’s code of conduct, including prohibiting forced, child, indentured and prison labor;

- ensures that the work environment is in compliance with applicable labor and employment laws, as well as the company’s code of conduct; and

- has not and will not, directly or indirectly, engage in certain activities connected to forced, child, indentured or prison labor. These activities should be expressly detailed in the certification.

3. Design due diligence forms and audit programs to evaluate and address risks of forced, child, indentured and prison labor in the company’s supply chains.

4. Develop and publicize internal accountability standards for employees and contractors in the company’s supply chain management and procurement systems regarding forced, child, indentured and prison labor.

5. Determine whether suppliers have appropriate systems to identify risks of forced, child, indentured and prison labor within their own supply chains.

6. Train employees, independent contractors and business partners, particularly those with direct responsibility for supply chain management, concerning the company’s expectations regarding forced, child, indentured and prison labor, particularly with respect to mitigating risks within the supply chains of products.

Given the growing regulatory regime, businesses should take steps on the front end rather than risk exposure. The TFTEA, along with the recent UK Modern Slavery Act of 2015, the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act and the Federal Acquisition Regulation on Human Trafficking in Government Contracts, shows how critical it is to eliminate trafficking, slavery and other forms of forced labor risks from supply chains. In addition to the risk of seizure, businesses may face reputational damage, contract termination, class actions and other potential liabilities. Anti-trafficking measures may also improve public relations and employee morale, as well as helping to eliminate the scourge of modern slavery. More information is available in the White House press release on the TFTEA.

© 2016 Perkins Coie LLP